Our Teacher Shortage is a Crisis. Here’s How We Can Fix It.

By Brian O’Connell | Executive Director, Golden Apple Foundation of New Mexico | December 13, 2018

Teaching is America’s most important profession. That’s no sappy platitude: the American workforce is the teaching workforce. There are more people employed as educators (teachers, principals, educational assistants) than in any other profession in America, other than retail. Why isn’t teaching considered a great gig? There are hardly any careers that offer more variety of locations and specializations. Job security is high; public sector benefits like retirement and health insurance are usually competitive with proximal alternatives. And yet, with all of this variability, flexibility and security, teaching in America has one very important drawback: nobody wants to do it anymore.

Who’s to Blame?

The shortage of classroom teachers in America is growing quickly. Finger pointing happens in all directions. Career K-12 teachers blame their principals and districts for shoddy management. Principals and districts blame state legislatures and departments of education for withholding funds and resources. State legislatures and departments of education blame teacher preparation programs for allowing unqualified graduates to receive certification. Colleges blame low student performance on (do you see the circle closing?) the allegedly shoddy quality of their K-12 teachers.

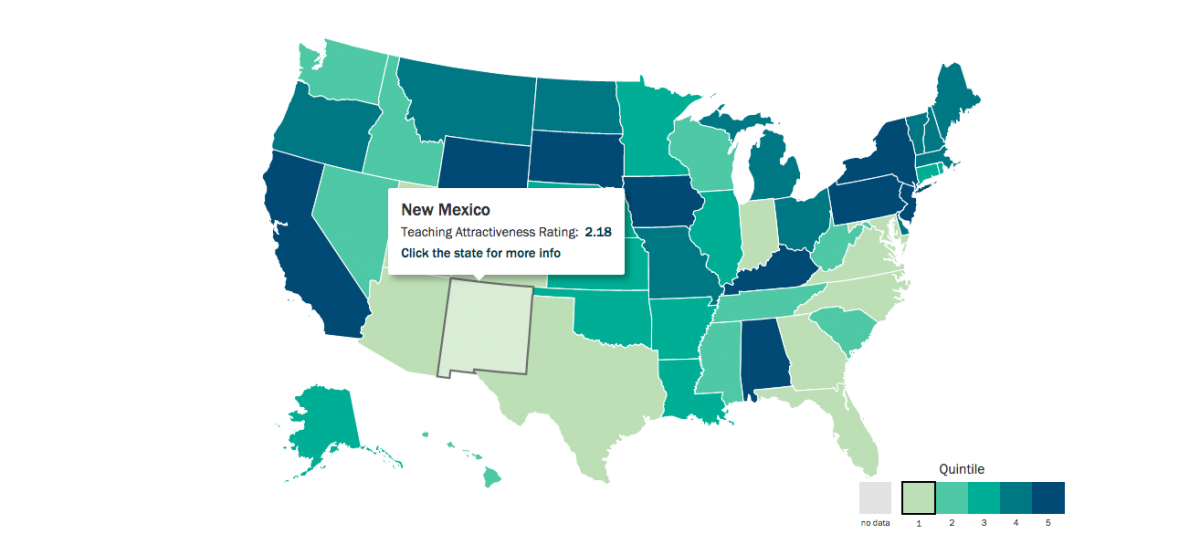

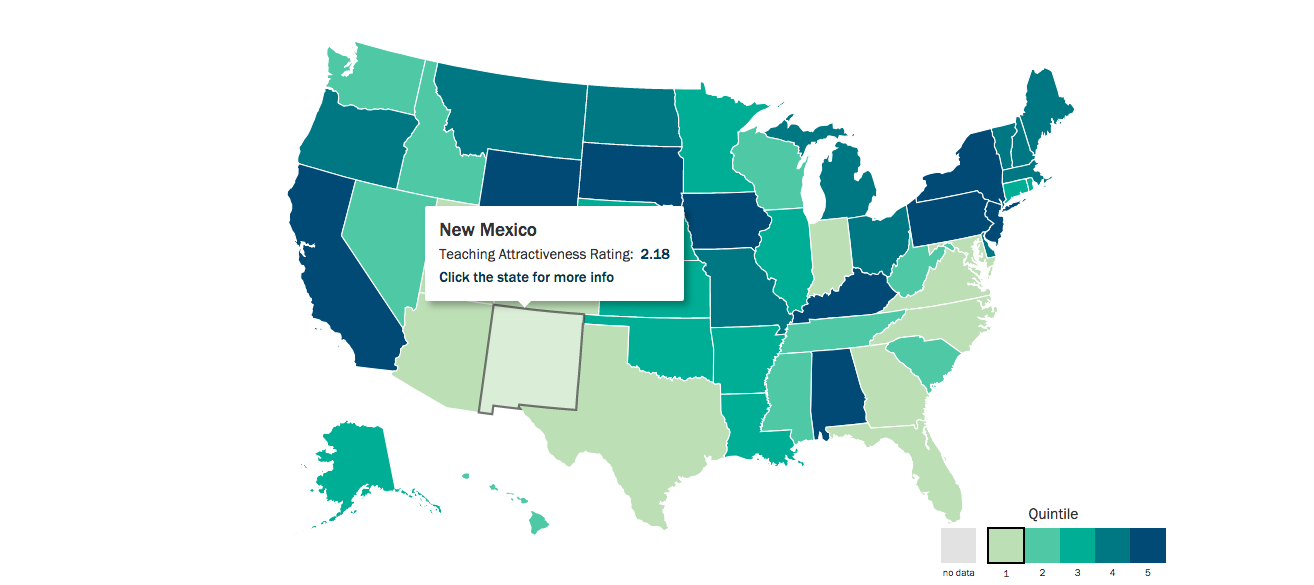

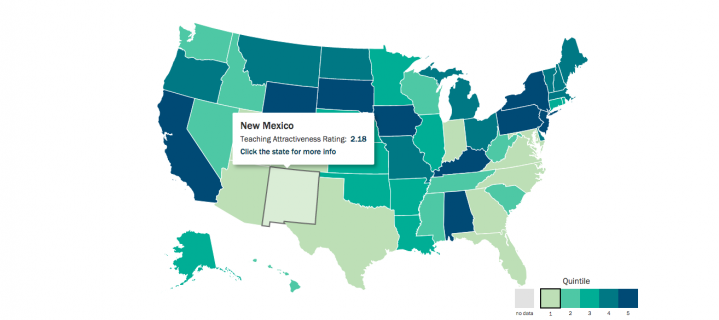

As this cacophony of blame hovers over the growing problem, the fundamental causes continue quietly taking root. In New Mexico, as an example, the trends within the teacher workforce are alarming. According to a 2016 study by New Mexico State University, vacancy rates among teachers of bilingual students, teachers of math and science, and teachers of students with disabilities are particularly high. In rural areas these vacancies result in classes being covered by teachers with other qualifications, ballooning class sizes, or the elimination of course offerings from the curriculum altogether. In more urban schools, districts try to offset the consequences by plugging in long-term substitutes. Teacher quality is compromised by the scarcity, and the results are observed in stagnant or dropping student achievement.

The immediate crisis is compounded by the knowledge that help is not on the way. Enrollments in teacher preparation programs are dropping precipitously (down 58 percent between 2012 and 2016 according to a report by the New Mexico Legislative Finance Committee). Persistence rates are also dropping, as those fewer matriculators in education colleges are graduating at consistently lower rates (34 percent fewer graduates over the same four year period). Factor in an aging teacher workforce with fewer incentives to remain after retirement age, and you have a population of classroom teachers that is eroding from both ends.

Alternatives Aren’t Working

As a community, we have tried to implement a number of plausible and well-meaning solutions for the teaching shortage. Creating alternative pathways to the classroom for mid-career professionals from other fields is a popular intervention. In theory, alternative licensure is a great way to supplement the workforce with seasoned professionals that have navigated a career and have real-world experience. In the best cases that is exactly what happens, but in many other cases the lack of classroom management and child development experience makes their first few years of teaching exceedingly difficult.

Still other answers have been sought through economic motivation. Strategies to tie teacher pay to student performance make great sense theoretically, but so far few states and districts have made a sustainable, scalable connection between merit-based pay systems and improved teacher retention, much less improved student outcomes.

Time for a Culture Shift

The problem with these policy-based interventions is that they don’t address the underlying cultural origins of the teaching shortage. As a community we can change the way we think in three important ways to begin addressing the deepest roots of our shortage problem in teaching:

First, we can treat teaching like a career instead of a job. The famous business and behavioral science author Daniel Pink identifies autonomy, mastery and purpose as the three most important motivators for workers. As a community, we can be much more creative about creating career ladders, incentive systems and even local school cultures around the pursuit of autonomy, mastery and purpose for our teaching workforce.

Second, compensation really does matter. Time magazine recently reported that teachers are compensated significantly less than their similarly educated peers in other professions. We know that young people with aptitude in math and science often choose engineering or technology professions over teaching simply because of the difference in beginning opening salary. While much of the policy community has focused on chasing the effects of merit pay, the overall system has become non-competitive because of a lack of basic sustaining investment.

Finally, we have to remember that quality teaching is the most important school-based driver of better student outcomes. We must resist and counteract the prevailing sentiment over the last 20 to 30 years that teaching is easy and that anyone can do it. We have to stop believing that we can improve student outcomes without investing in teachers. We have to value them better -- through pay, in the way we portray them in media, and in the way we appreciate them on a personal level.

If we change our thinking in these three ways, classroom teaching will have a chance to compete with retirement on one end and every other career on the other end in the minds of potential teachers.

Brian O’Connell is the Executive Director at Golden Apple Foundation of New Mexico, a nonprofit working to catalyze teacher excellence through recognition, professional development and community engagement. Find out more at www.goldenapplenm.org