We Know Capstones Already Work, Why Aren’t We Using Them?

In my last article, I wrote about the harmful legacy of standardized testing, and how years of "teaching to the test" have left us with a standardized curriculum with little flexibility. Now, I would like you to consider what education could look like if educators were able to work together with students and communities to design curricula and assessments that celebrate and honor our diversity.

Take for example, the incredible transformation I witnessed at my own middle school in the early 2000s. I know this is ancient history for many, but those were the last years we were encouraged to implement project-based teaching, learning, and assessment.

Capstones In Action

Beginning in 1999, a teacher applied for and was awarded a grant to hire an artist who would work with students to create a ceramic tile mural that was titled “El Camino Real, A Journey of History and Culture”. The team of teachers developed a curriculum that would support the creation of the painted tiles and tell the story of this road.

We started by learning everything we could about this topic and assembling maps, pictures, poetry, historical stories, Native American and Spanish art of the 1500s, and information about modes of travel, plants, and animals common at the time. Each teacher then put together a unit in their subject area that would explore various aspects of the Camino Real and support the creation of the tiles that would then be assembled by the artist working with the 150 students. These units were developed within the scope of the standards and benchmarks of each discipline, along with an introductory lesson and shared culminating activity.

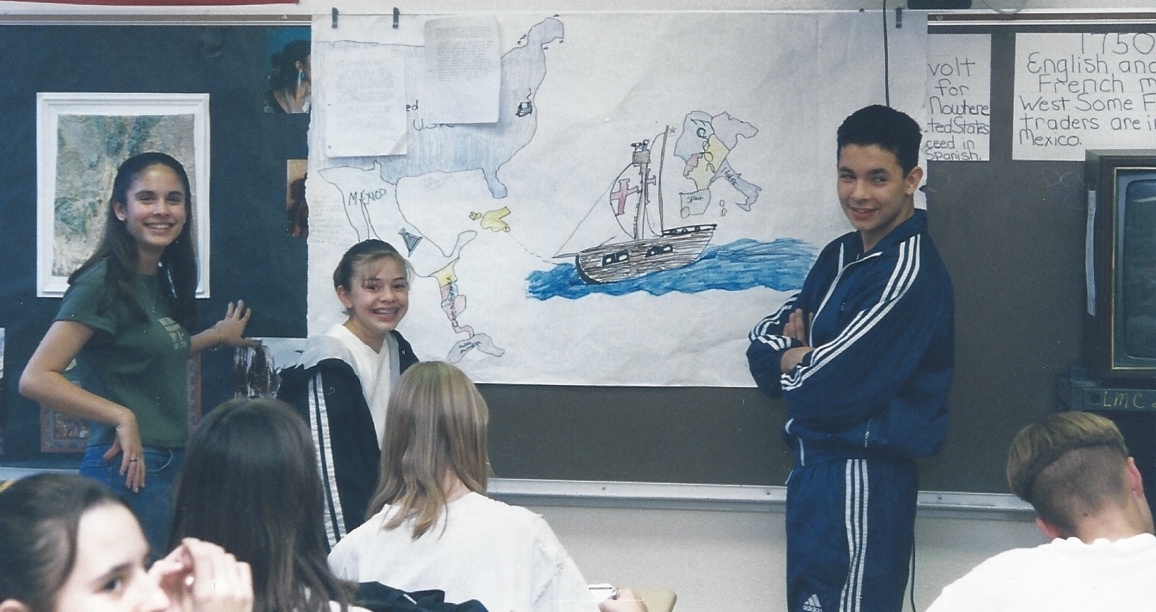

Students and teachers at Picacho Middle School created project-based learning curricula in science, math, history, and art that culminated in a ceramic tile mural. (photos courtesy of Mary Parr-Sanchez)

All students read, researched, wrote, mapped, and created individual tiles for inclusion in the mural. Students documented progress in all their classes by taking pictures and writing stories throughout the unit. Speakers from the community spoke to students about the history, art, plants, animals, and peoples that collided on this road, creating the diversity of cultures and languages we enjoy in present-day New Mexico. The consideration of multiple historical perspectives was encouraged by using writing prompts from all viewpoints, like asking students to consider how Native Americans of the time responded to the arrival of the Spanish explorers and vice-versa.

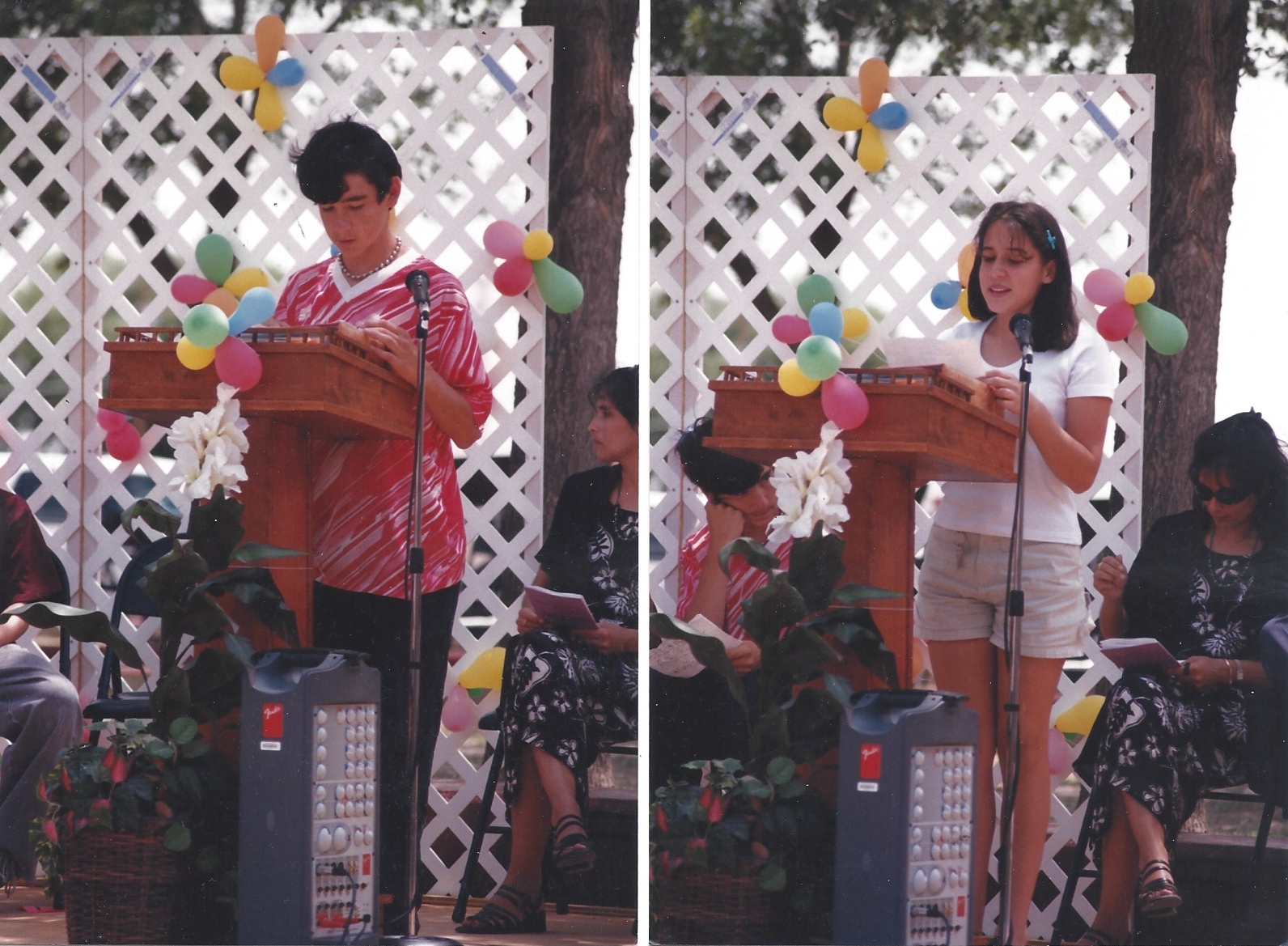

The culminating activity, in 2000, was the unveiling and presentation of the tile mural to the City mayor, school board, parents, and all other students and teachers in the school. The band played music from the time, the family and consumer science classes provided refreshments to the guests, some students developed and made the program for the unveiling, while other students worked on presenting the mural in a prepared speech.

(Top) Students present their work at the public unveiling of the capstone project in 2001. (Bottom) The final mosaic titled “El Camino Real, A Journey of History and Culture: A Mural Project” on display in Las Cruces, New Mexico. (photos courtesy of Mary Parr-Sanchez)

Proven Success

This is only one example. We would do several project-based learning units like this a year, and students loved it! We would have students save all their work in a portfolio for each of their classes. At the end of the year, they would reflect on their learning by writing an essay in each class about those units and activities they liked the most or during which they felt they had done their best work.

The team of teachers would then bind these essays together and have the students develop a presentation about that work for their final capstone assessment, to which they were encouraged to invite family and friends. Students could present in English or Spanish, and could dance, sing, play an instrument, write a screenplay, give a demonstration, or show their learning in another way. These presentations allowed teachers, parents, and students to recognize and celebrate the individual talents of all involved, talents that would go unremarked on a standardized test.

Initially, only one grade level would do this type of capstone presentation and ceremony, but as time went on and the success of the program became known to the entire school community, eventually all teacher teams and grade levels participated.

We had 99% of our parents show up to these important, student-centered and student-led events. We all learned and grew from these experiences, and we got better each year. We educators held each other accountable for the success of all students.

When the Tide Changed

Unfortunately, by 2007, this school-wide tradition was shut down by the new Superintendent. He had never attended any of the presentations, but he said that we would be using a standardized assessment for the end of the year instead.

He wanted us focused on the exam, and he wanted our students focused on it as well. More than ten years of incredible work was abruptly ended and much of the excitement in the school withered thereafter.

Use What Works

As you can see from this example, project-based learning and capstone assessments are nothing new. They are not an empty promise of innovation nor are they another burden on fatigued educators.

In fact, using assessment as an instrument of learning is the most organic and authentic way for educators to teach and for students to learn and demonstrate their learning. We at NEA-NM believe that educators must have the autonomy to design assessments that are responsive to the needs, interests, and talents of their students and which involve families and the community in the process of learning.

New Mexico is on an exciting path toward reintegrating capstones into our assessment system. The Graduation Equity Initiative is piloting graduation profiles and senior capstones as options for graduation. If you are a teacher or district leader interested in advancing this important innovation, we encourage you to join the Innovative Assessment Community of Practice.

Stand with us and our partners at Future Focused Education as we advocate for capstone assessments for New Mexico now!

The New Mexico Graduation Equity Initiative is piloting a new project-based graduation pathway that culminates with capstone projects as an alternative to traditional testing. Learn more and join the movement here.

Read more in our Equity in Education series, tracking the progress of the New Mexico Graduation Equity Initiative.