What It Looks Like When Classrooms Are Truly Embedded in Community

"What do you want to be when you grow up?" This is a question we ask students numerous times, and one that we as educators, parents, or adult members of our community may continue to ask ourselves.

Schools often focus on the skills and knowledge students need to navigate their chosen path, but do all students know about the numerous career paths around them? Have they seen community members at work in those chosen fields?

What has become increasingly apparent, and maybe exacerbated by these pandemic years, is that students may not know who or what makes up that world of career, college, and other frameworks of social mobility. If they haven’t seen what or who is out there—even within their own communities—can we expect a student to definitively picture the breadth of who they can be?

Programs like CommunityShare are responding to the need to foster hands-on learning experiences by reconnecting classrooms with the community around them through project-based learning.

Research has shown over and over that engaged learning—especially project-based learning—is what students need to retain knowledge, experiences, and to personally identify what they find meaningful. Engaging with the community, and especially with adults who share their interests, shows a student that what they care for is important, valued, and worth growing beyond the classroom.

Representation in Motion

Marcus, a high school sophomore, wasn’t in social or community groups outside of school. His view of culture was nurtured by his family and friends, but beyond those circles, he wasn’t sure what or who made up Las Cruces and its integration of cultures that turn a city into “home” for many communities. At school, his teachers used standard New Mexico history textbooks, and while he saw some of his own traditions represented, the static and sometimes outdated information didn’t always feel connected to actual people.

He wasn’t connecting to his learning, and his learning wasn’t connecting how people like him have shaped narratives seen in textbooks. Perhaps he’s read about how Mexican and Indigenous cultures have informed art and food in our region, but if he doesn't see that people around him are more than just distant echoes of key people represented in history books, he might not contextualize how the person he is already is—an admirer of his amásání’s (grandmother) weaving patterns, his neighbor’s farm-hand, and an already skillful cook of traditional Mexican dishes—informs much of what he can do as he grows up and into his communities.

It would be one thing to show Marcus a PowerPoint presentation on how local pecan farmers and Navajo weavers have connected Las Cruces with the world since the early 1900’s, but it would be another experience entirely to bring small business owners, entrepreneurs, and local organizations into the classroom to have them share their crafts and services with students. To round out this project, inviting students to the downtown Farmer’s and Crafts Market to see these community partners in action would allow Marcus to see first-hand how a Diné weaver who uses a traditional loom, a food truck that serves authentic Mexican food, and a clothing line founded by California transplants all nurture a growing community that is distinctly Las Cruces.

Additionally, seeing people who may look like them thrive in different vocations, creative spaces, and the spaces in between can show that the “real world” does have a place for us all if we’re willing to explore inward as much as we are forward.

Fostering Belonging

This sense of belonging is one that the Kindergarten to College or Career Coalition continues to explore more deeply by looking at equitable resources and career availability within Las Cruces. Erica Surova of this coalition and the Center for Community Analysis asked the following:

- Do we have careers locally for graduates?

- Are students supported in career exploration along the way?

- Does our society undervalue certain careers?

Furthermore, representation within careers can also be as impactful as the representation of the career itself. Marcus may never have met a male yoga and mindfulness instructor in his own elementary advisory period. But this spring, students at Alameda Elementary will meet a male teacher in a field that they might see as being female-dominated. They’ll learn that someone can make a living and a difference as a wellness coach. Students also get to pick up more healing-oriented resilience skills like belly-breathwork, or learn words to describe their increasingly complex feelings—skills that, more often than not, are accessed only in pricier therapy sessions or corporate retreats.

Thanks to a vermicomposting project with Dr. Emily Creegan, a 6th grade student at Lynn Middle School was delighted to learn that his knowledge about compost can eventually lead to a career. Dr. Creegan, an environmental restoration specialist and instructor and course developer at Johns Hopkins University, has collaborated with Ms. Coryell and her gardening class since spring of 2021.

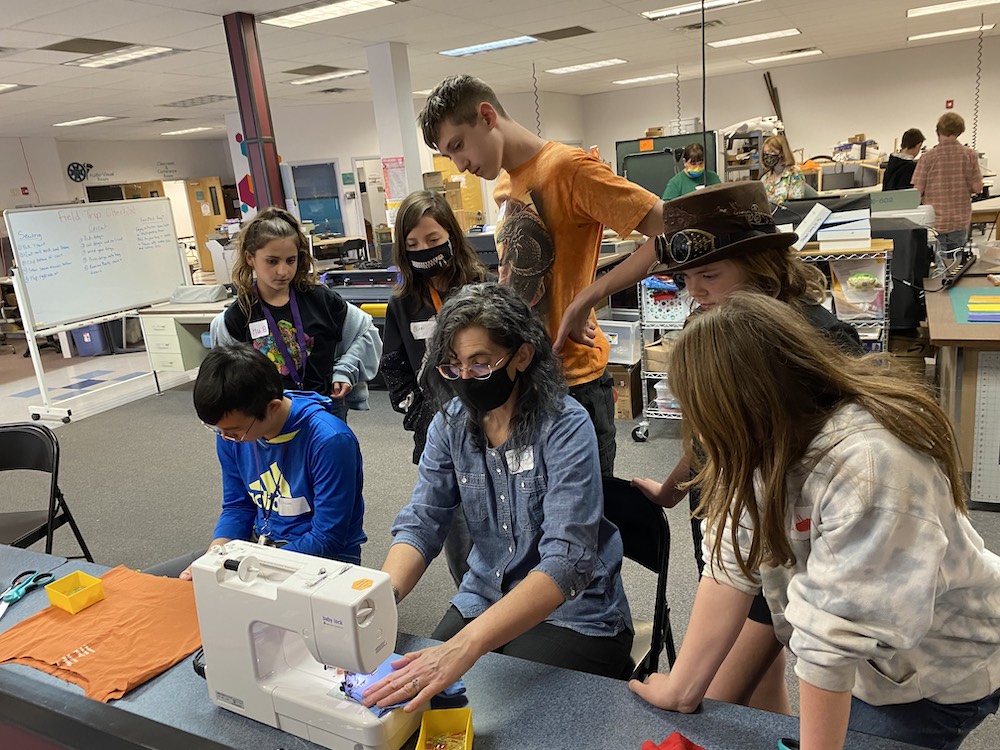

By securing a small grant through CommunityShare, they are exploring how varieties of vermicomposting systems can help reduce the environmental impact of food waste. As students are researching how reducing, reusing, and recycling can help the environment, they are internalizing how they can broaden their care for the world and its living resources. These gardening students have gotten to literally put their hands on the project, smell nutrient-rich compost, and shout in surprise as they handle wriggly worms they’ve deemed either “cute” or “disgusting”.

This project also involved a “waste audit” where students sorted through their waste bin (with gloves and masks!) and classified an item as compost, recycle, or waste. They realized just how much they could recycle or turn into garden compost which, in turn, grows nutritious vegetables. Students also deeply connected with the idea that while it was “super cool” to see a scientist who happens to be a woman speak with such purpose, they don’t need a doctorate to make a difference every day. They can meaningfully contribute to change through actions as modest as throwing uneaten pizza crusts into the compost, or by upcycling old clothes to make reusable grocery bags.

Perhaps most poignantly, the handful of students who remarked that the waste audit was “just so, so gross” could understand that careers with less glamor are nonetheless incredibly impactful. According to Dr. Creegan, at least one student in every group shared that they were shocked by how quickly things like unfinished cereal could deteriorate, and they would “never forget this lesson.” Environmentally impactful and socially responsible, students built sorting systems, delegated responsibilities among fellow classmates, calculated measurements for compost bins, mastered different tools, and played in the soil and sun for a short time. These kinds of hands-on projects have engaged more senses, abilities, learning preferences, and out-of-classroom learning opportunities than a worksheet could try to cover.

Learning that Humanizes

Wellness coaching and waste-to-resource management are areas that feed ongoing conversations about what we consider as knowledge in schools, or what makes a job “important”. Community-involved learning opens doors to important opportunities like career prep, but just as significantly, humans young and old learn to humanize one another.

Students are told to think about the future, and adults are told to think about the children—yet in order to do either, both must see each other, regarding the other as the “realest” part of the real world. Without that personal connection, we’re led to the kind of interpersonal and socio-intellectual isolation that renders mindfulness exercises as experiments, or anything relating to waste management as “dirty work”. Everyone has something to offer, and “everyone” is a lot closer to home than we may anticipate:

- The relative who taught you how to play a card game

- The neighbor who fed your dog while you took on more work hours

- The teacher who shared they believe in you

- The friend who knows a guy who knows a gal who can fix cars

- The first person to write you a letter of recommendation

These relationships are all forms of social capital, and students need these interpersonal bonds and informational bridges just as much as hard and soft skills. Bonds and bridges nurture socio-emotional expansion in all directions, and they set more deeply-rooted foundations whereupon social mobility can sprout up/outward. Social capital is also inherent to community-involved learning. Yoga instructors or scientists alike can empower and personally connect with students, but not just because of similarities (or even differences) in the environments through which they were brought up. They connect because of shared interests and values, like caring for what and who we have. Those who can share and integrate their life-long, dynamic learning experiences into classroom learning experiences are precisely what CommunityShare hopes to bring to more students throughout Las Cruces.

As students confidently voice who they are by learning, building, and rebuilding their world alongside community partners, perhaps instead of asking “what do I want to do when I grow up?” they can assess: “Who I am is enough—what is something in the world I can change for the better?”

Find out more about the Las Cruces CommunityShare program here.

References

Avallone, A. (2018. Jul. 20). You Know Who: Building Students’ Capital. EdWeek. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/opinion-who-you-know-building-students-social-capital/2018/07

Buck Insitute for Education. (2022). Project Based Learning. PBLWorks. https://www.pblworks.org/why-project-based-learning

Buck Institute for Education. (2022). What is Project Based Learning?. PBLWorks. https://www.pblworks.org/what-is-pbl

Carreon, C; Nayra, A. (2021). CommunityShare! Presentation [PowerPoint Slides]. Google Slides. https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/11J1FRniuuSThw18VdbdPxJyDem7d4Ok4/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=102935568050924466529&rtpof=true&sd=true

Madda, Mary Jo. (2019. Jan. 9). For Students to Succeed, Social Capital Matter Just as Much as Skills–Here’s Why. Ed Surge. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2019-01-09-for-students-to-succeed-social-capital-matter-just-as-much-as-skills-here-s-why

Surova, E. (2021. Nov. 16). Kindergarten Through Career in Dona Ana County [PowerPoint Slides]. Microsoft Excel. . https://webcomm.nmsu.edu/cca/wp-content/uploads/sites/72/2021/11/K-Career-Coalition-Presentation-Nov.-16-2021.pdf

Comments

awesome