Does School Segregation Affect Student Success?

“Modern school segregation is driven by systemic inequality. Existing residential segregation in U.S. neighborhoods spills over into schools, dividing school zones by race and socioeconomic status.”

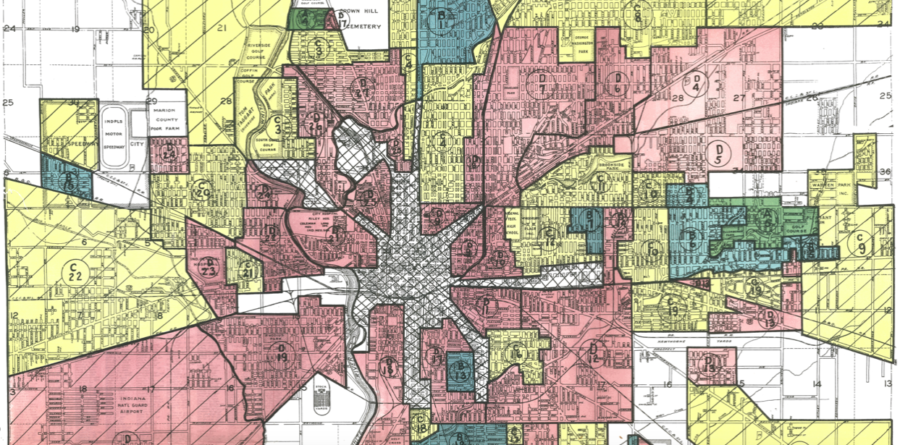

Many Americans are unaware that school segregation still exists. In the 1950s, school segregation was deliberate and explicitly racist. Today, racism continues as parents protest integration plans and districts gerrymander school boundary lines.

Although it has been nearly 70 years since the United States Supreme Court made enforced school segregation illegal in public schools, it remains pervasive across the United States—including New Mexico.

What’s Happening in Las Cruces?

In Las Cruces, our local population is growing, and there is a projected need for more primary schools. Before we build new schools and draw school boundaries, we needed to examine how segregation can inhibit student success and how integration can promote equitable educational outcomes for our children.

With this in mind, the NMSU Center for Community Analysis initiated a study to examine school segregation in Las Cruces and school attendance boundaries or "catchment zones," one of the main drivers of school segregation today.

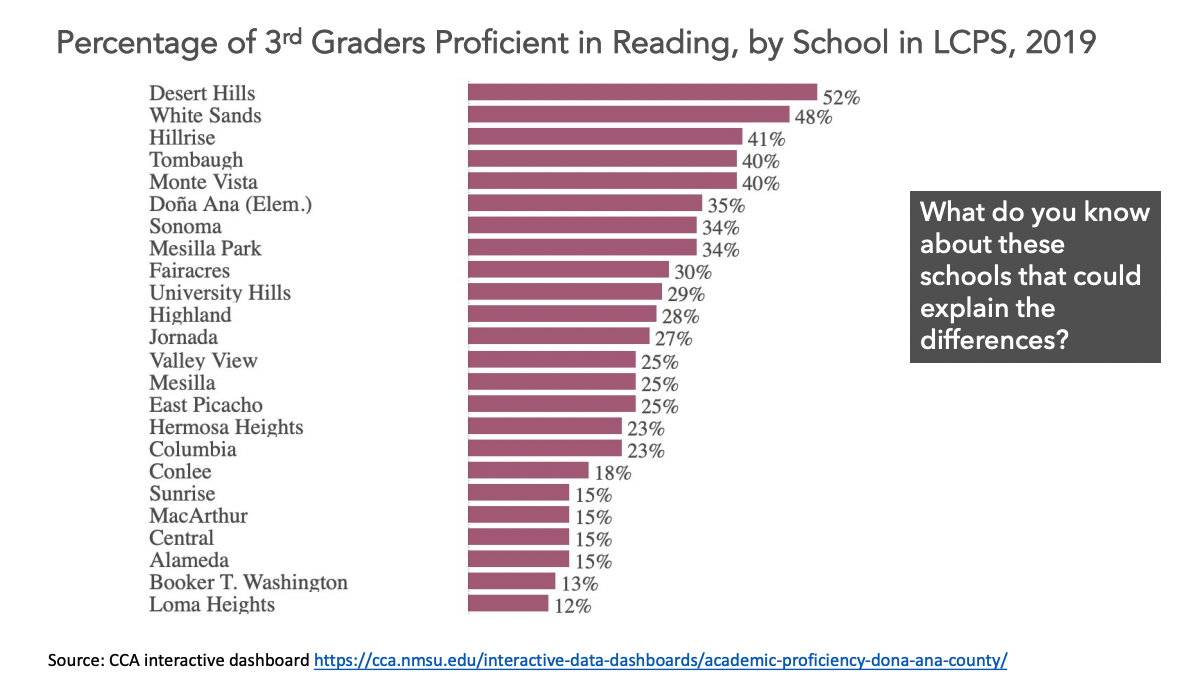

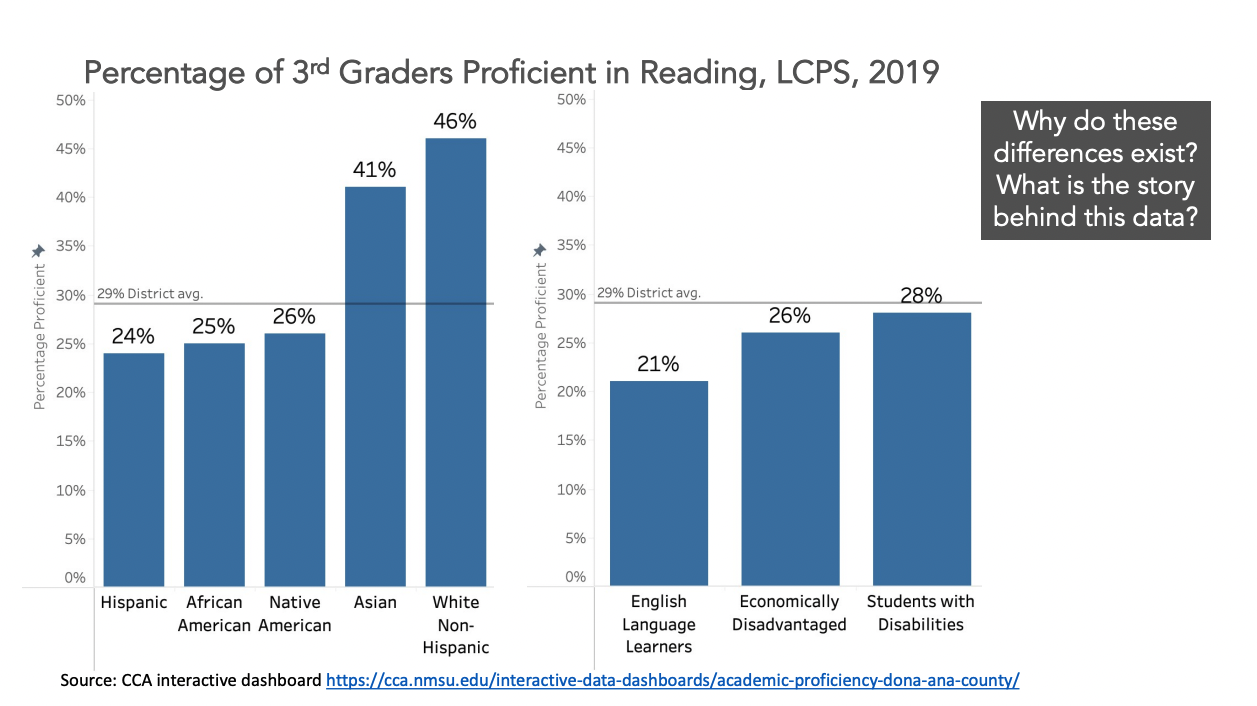

Our research revealed that Las Cruces public and charter schools are deeply segregated by race, income, language, and disability status—driving a local achievement gap.

Why Segregation Matters

For example, at Loma Heights, an elementary school with one of the highest poverty rates in the district, only 12 percent of third-graders were proficient in reading—compared to 52 percent proficiency in Desert Hills Elementary, a low-poverty school.

School segregation has a profound effect on student outcomes. Research by the U.S. Department of Education shows that low-income students who attend a school with low-poverty poverty rates are 70 percent more likely to attend college than if they attend a high-poverty school.

Modern school segregation is driven by systemic inequality and a lack of forethought. Existing residential segregation in U.S. neighborhoods spills over into schools, dividing school zones by race and socioeconomic status. White, non-Hispanic students often have greater access to high-performing, low-poverty schools. In contrast, students of color and other marginalized students are disproportionately assigned to high-poverty schools that often lack the funding and resources to serve them.

Our new story map shows how health and social inequities are concentrated in certain Las Cruces neighborhoods, so it stands to reason that some schools will need extra resources to close the opportunity gaps.

School Boundaries and Student Success in LCPS

School catchment zones (also called school attendance zones or boundaries) are defined as the geographic residential area from which students are assigned to a local school. Districts often draw school catchment zones to capture neighborhoods closest to a “neighborhood school.”

Therefore, school composition often replicates existing housing segregation unless school districts use socioeconomic neighborhood data to draw boundaries that intentionally integrate students from diverse neighborhoods.

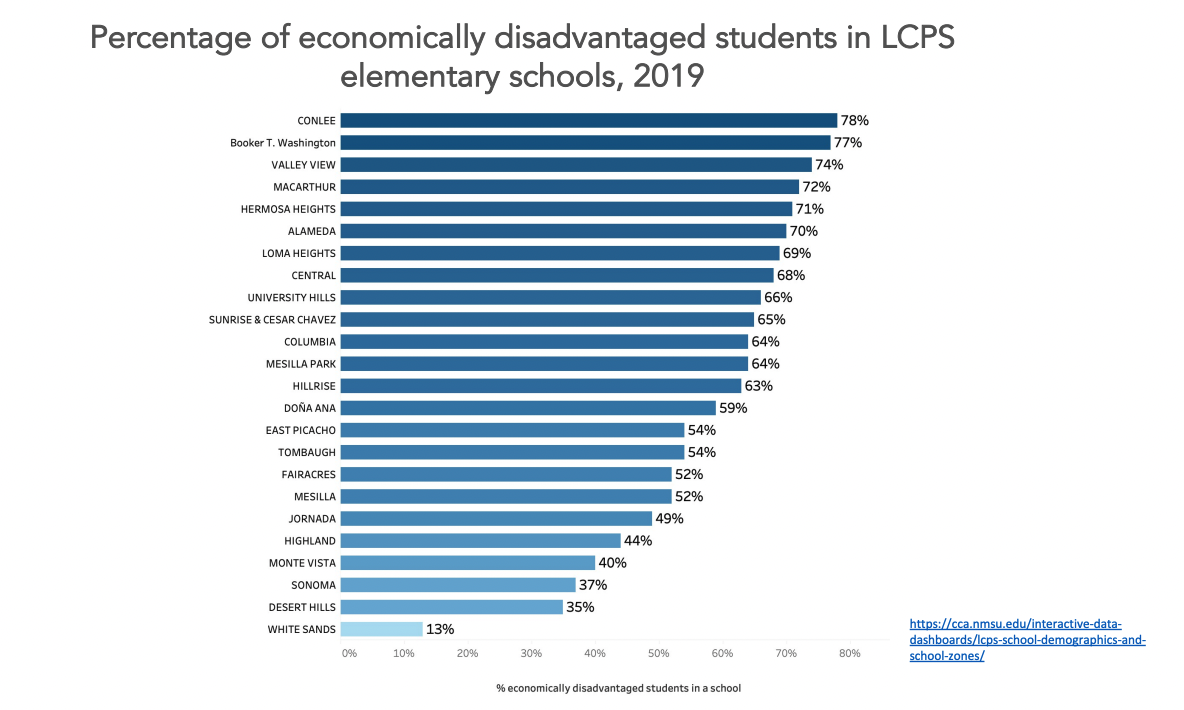

Our analysis in LCPS found a sixfold difference between the highest-poverty elementary school and the lowest-poverty elementary school. This is concerning because of the relationship between poverty and student outcomes. Students in high-poverty schools often do not have the same educational opportunities as students in wealthier schools. Students in low-poverty schools tend to have more access to challenging coursework such as advanced placement classes, higher qualified teachers, and higher expectations for students.

In LCPS, 56 percent of all elementary students are considered economically disadvantaged. In some schools, as many as 78 percent of students qualify as economically disadvantaged while in others the number is as small as 13 percent. The implications of this are profound since it is much more likely that a student of color will be assigned to a high-poverty school than a white, non-Hispanic student, deepening the opportunity and achievement gaps between students.

The effect of segregation is obvious. In LCPS, nearly half of white non-Hispanic third graders are proficient in reading compared to approximately one out of four Hispanic, African American, or Native American students.

Dynamics of COVID and Housing Shortages

In LCPS, some elementary schools were at overcapacity before the pandemic, which will inevitably force the district to add more schools and redistribute students by altering the school catchment zones.

The pandemic exacerbated housing inequality and instability, with rents hitting all-time highs and many cities experiencing housing shortages. Moreover, although births continue to decline in New Mexico, urban areas in New Mexico have continued to grow due to an increase of residents from rural counties moving to larger cities and residents from other states moving to New Mexico. This has strained the affordable housing market, leading the Las Cruces City Council to explore building affordable housing units. In addition, the growth in housing developments and increased population have led to three new schools added to the district in the past ten years, and there are plans to add more.

What do we do now?

There are many ways to counteract the adverse academic outcomes of segregation. The first step is to promote school integration, inclusion, and equity. Careful consideration of socioeconomic neighborhood data can help to diversify school zones when drawing school boundary lines. Family and community voices must be a part of any rezoning process.

We should also consider the intricacies of school choice policy. Research indicates that school choice without desegregation efforts often increases school segregation since "choice" is related to access to information, transportation, and resources that are not equally accessible to all families.

Beyond integrating and diversifying schools, we must also consider equity and inclusion within the schools. We must embrace multilingualism and decolonize curriculums and practices. We must increase access to advanced placement and dual credit classes for marginalized populations.

We must support community schools as Las Cruces continues to grow its community school model. Community schools offer a wide variety of community-based supports and services and high-quality learning opportunities.

Erica Surova is the Director of the Center for Community Analysis at New Mexico State University. She holds a Master of Arts in Sociology and a Master of Applied Geography from NMSU and has spent over 18 years working in education as a teacher, researcher, and program director. In her current role, Erica and her team partner with organizations across the county and state to collect, centralize, analyze, and visualize data to improve education and health outcomes for children and families in New Mexico.

Erica has conducted numerous surveys, evaluations, and studies on advancing education and social equity in New Mexico and has helped multiple organizations strategize how to improve evidence-based decision-making and collective impact through data and evaluation.

References

- 2020 Census Demographic Data Map Viewer, Population Change

- Las Cruces Public Schools Facility Master Plan 2019-2024

- CCA Dashboard: LCPS School Demographics and School Zones

- CCA Dashboard: Academic Proficiency in Doña Ana County and New Mexico

- Education Context Report, Doña Ana County, 2020

- https://cca.nmsu.edu/documents/K-Career-Coalition-Presentation-Nov.-16-2021.pdf

- School segregation and racial academic achievement gaps, Reardon 2016

- Concentration of public school students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, The Condition of Education 2020

- Unequal opportunity: Race and education, Darling-Hammond 1998

- PICS one year later: Reflections on the anniversary of the Supreme Court's voluntary integration decision, The Civil Rights Project 2008

- Decolonizing our classrooms starts with us, Kawi 2020